|

|

News

A message for Holy Week and Easter

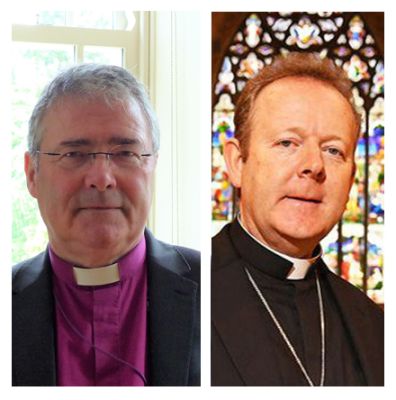

From Archbishop John McDowell and Archbishop Eamon Martin

Archbishop John McDowell and Archbishop Eamon Martin.

In the Christian calendar, Holy Week has sometimes been referred to as ‘The Week of Weeks’. All of the Gospel writers devote about half the content of their books to recounting in diverse ways what happened to Jesus and his friends in that dramatic week, and in drawing out the meaning of those events:

• Jesus setting his face towards Jerusalem;

• The welcome he received and the subsequent rejection he experienced;

• His desire to be obedient to his vocation from the Father;

• The scene in the Upper Room, where in word and sign he anticipated the manner of his death and gave the Church the sacrament which is both a source and an expression of the grace which lies at the heart of our mission;

• His arrest in the garden, under the paschal moon;

• His betrayal by a close friend and his denial by another before the cock crowed at dawn;

• His “trial” before the keepers of orthodoxy in Israel, and then before the civil magistrate whose casual cynicism has marked him out as one of the dark figures of world history;

• The courageous little group mostly women who “…stand not far off…” and the reordering of relationships at the foot of the Cross: “Woman behold your son; son behold your mother…”

• The sordid, lonely and ignoble death which has given the world its most powerful religious symbol, the Cross;

• The kindness of strangers in his burial;

• The abject bewilderment of his followers, lying on the floor in the dust behind locked doors;

• The various encounters by women of the risen Lord, unrecognised, but somehow known;

• The dawning conviction that everything in every age has been changed utterly.

Centuries of spiritual reflection and theological debate have led to acceptance that the death and resurrection of Jesus was somehow an atonement that brought about a reconciliation. This year our commemoration of the ‘Week of Weeks’ is all the more significant and poignant given that we mark 25 years since an historic agreement towards lasting peace and a resetting of relationships within and between these islands. That the Agreement was reached on a Good Friday gives it a special resonance.

Have we, in the Christian community in Ireland, allowed ourselves to forget the greatness of this achievement, the sacrifices and risk-taking that made it happen, the light it shone into the darkest of days and the promise and hope it offered?

Have we been open to establishing the full truth of our past, so as to enable justice and facilitate forgiveness and healing?

Might it be time for those of us who call ourselves His disciples, signed at baptism with the sign of his Cross, and who recognise, however dimly, the cost of our reconciliation, be prepared to make our own sacrifices and atonement for our carelessness with the precious opportunity for lasting peace that has been given to us?